How the de Heem Family Shaped Dutch Golden Age Food Still Lives

Ready to get decadent? Jan Davidsz. de Heem was born at the peak of the Dutch Golden Age of painting. With a little guidance from his father (also a painter), he went on to create some of the most mouth watering pieces of the era. With overflowing banquet tables and bountiful festoons portrayed in dramatic shadow, he managed to become one of the most in-demand artists in an era overflowing with art.

In his lifetime, de Heem had an uncanny knack for balance. One painting ties together a billowing cloth to bowl of bright red fruits with spiral of lemon peel, cascading off the edge of the table it rests on. Another uses translucent grapes, reflective silver, a blue and white porcelain vessel to combat the dull darkness of a heavily shrouded background.

This embrace of chiaroscuro elements made de Heem one of Anwerp’s most prolific and popular artists. His skill was to take the drama bursting from a Caravaggio or Vermeer and compress it into a single table setting or collection of fruits. In short, his work influenced thousands of Dutch Golden Age food still lives.

At the height of his career, Jan Davids. de Heem recruited his sons to join him in his workshop. In short, he simply could not keep up with commission demands with just two hands and one ming. Therefore, his sons would composite the “bones” independently. Afterwards the elder would retouch each piece and sign. Through this collaborative business, both Cornelis and Jan Janszoon became master painters in their own right.

This, in our opinion, is where the story truly becomes interesting. The de Heem brothers are a unique case study in that they have a nearly identical background and a shared prime influencer (their father). However, as the two men picked up on the basics, they diverged into their own separate entities.

Cornelis de Heem was the product of Jan’s first marriage with Alette van Weede. He learned to replicate his father’s work, but when left to his own devices, he began to explore on his own. He traded in the grand canvases his father’s clientele often demanded in favor of small works. Despite implementing a “coarser brush”, he brought in lighter colors that would never fit in with his father’s more dramatic palette. There were certainly nods in subject matter to the Dutch Golden Age food still lives his father had produced before him. There’s no shortage of citrus peels or fresh cut flowers to be found. But, every now and then Cornelis would stray entirely from his source material. Just below of birds copulating, you might encounter a particularly vulvic melon resting on a tabletop.

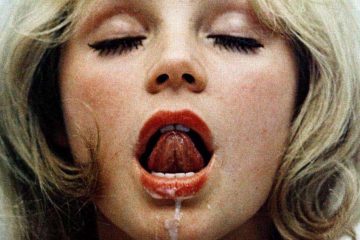

After Alette’s death, Jan Davidsz de Heem met Anna Caterina Ruckers, who bore him Jan Janszoon de Heem. Even as he grew into a brilliant painter in his own right, he never strayed far from his namesake. In fact, their work is at times nearly indistinguishable. They both signed their pieces J de Heem, further blurring the line on where father ends and son begins. However, there are instances in which the younger de Heem strayed from the decadence present both his father and brother specialized in. One example featuring little more than a tobacco pipe and a glass of beer features the same stylistic features that made his father’s work so beloved. However, lacking the whimsy of a flowering festoon or a bountiful banquet, Jan Janszoon’s humble subject matter is a stark departure from the Dutch Golden Age food still lives his predecessors mastered.

It’s hard to definitively say which brother was more successful. There’s merit to diverging on your own route as much as there is learning the ways of old masters. Regardless it’s fascinating to speculate what led them down their own separate paths.