Wayne Thiebaud’s Postmodern Food Art will Satisfy your Sweet Tooth

While artist Wayne Thiebaud doesn’t consider his work to be Pop Art. However, his postmodern food art has a similar presence to the graphic works of Lichtenstein and Warhol. Bubblegum colors pop off of canvases in geometric blocks. Features are exaggerated and simplified. Primarily focusing on the eateries and foodstuffs that people clamor for, his brand of still life is a far cry from the photorealistic content of the old masters. Before the Campbell’s Soup Cans became an icon, it was Thiebaud who was paving the way for postmodern food art.

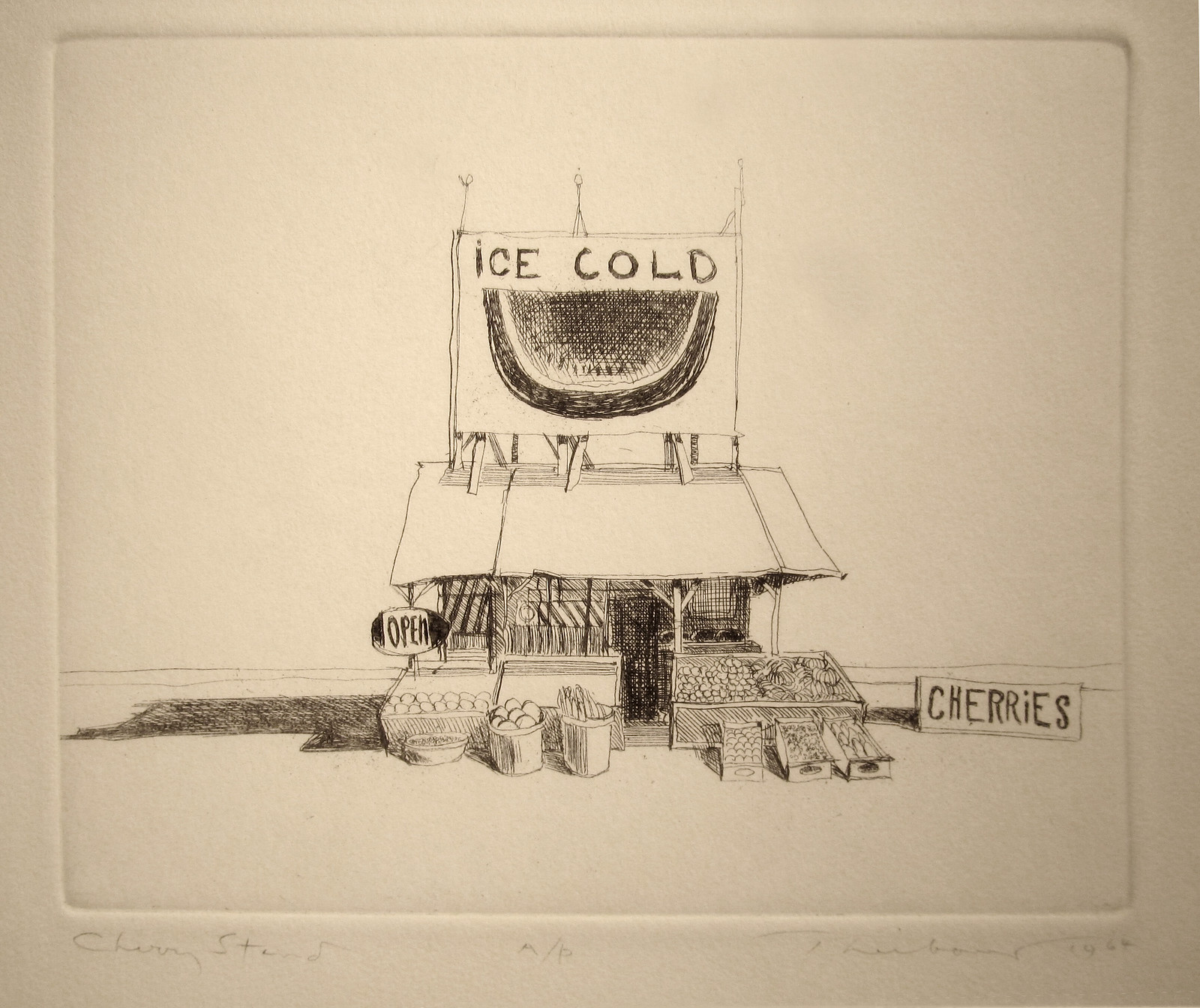

Drawing inspiration from abstract expressionists and Baroque realists alike, Thiebaud’s style is poignant and unique. Interpreted by some as critical commentary on consumer culture and others as nostalgic reveries, his food centric artwork hones in on the familiar rather than the glamorous. There are no fine linens or brass carafes in sight. Instead, there’s a focus on the likes of the diners, cafeterias, and other public watering holes.

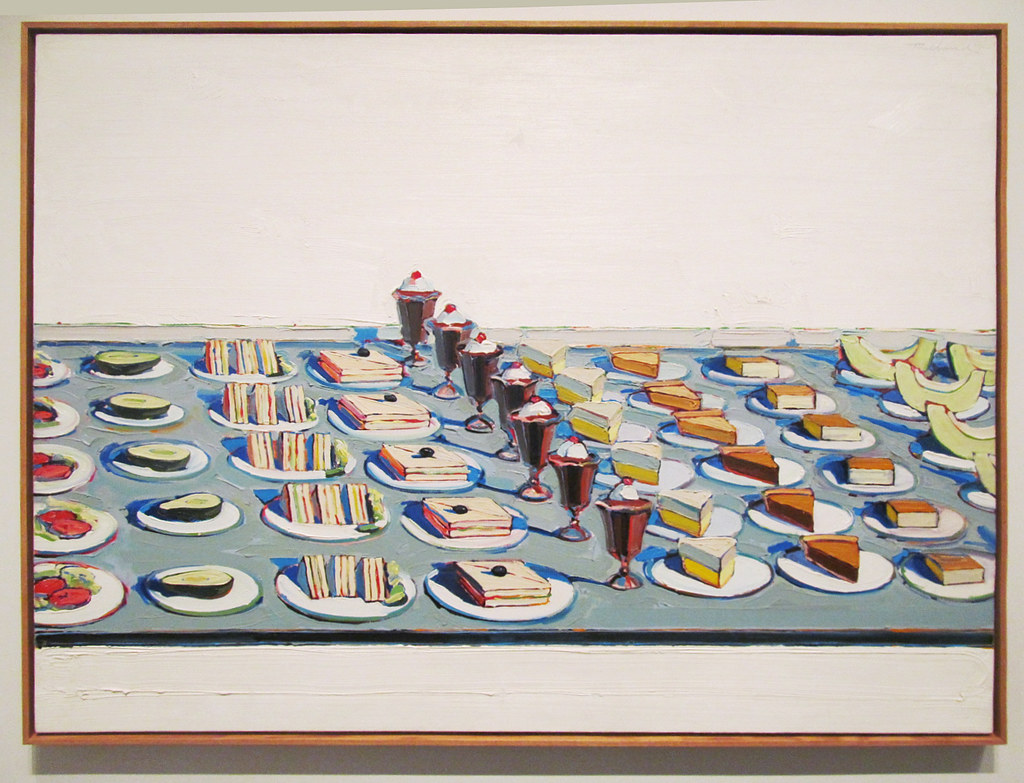

Subject matter isn’t the only thing that draws Thiebaud’s collection together. The artist has a fascination with repetition and pattern. Through his work, he reveals the attractiveness of cylindrical cakes on display at a grocery store. Tantalizing pie slices behind restaurant glass transform from tasty treats to aesthetically appealing icons.

Spellbinding tones and hues keep viewer’s eyes dodging across compositions. The artists once described his colors as “fighting” one another. Whether it’s a two toned food lithograph or an oil painting of two hundred tints, his works combat and compliment one another masterfully.

It’s easy to write off everyday routines and rituals as well as the objects we interact with daily. It’s easy to overlook food as little more than a necessity, taking for granted the array of flavors and feelings they have to offer us. Thiebaud’s decadent postmodern food art does something beyond displaying the novelties that comfort us most. Through striking colors and bold shapes, he forces us to acknowledge his subjects as something more than consumables. Instead, objects as humble as a slice of pie become works of beauty.