Love, Food, and Grief through Nobuyoshi Araki’s Lens

“After she was released from the hospital, the food she prepared was all the more full of love. There is no doubt that she knew that she only had one month left to live. I had been shooting color with a macro lens with a ring strobe, which I changed to monochrome. One table lamp, a tripod, F32, 1 second. I can never forget the sound of that shutter’s one long second. The meal was a love affair with death”

(translation from an excerpt of Nobuyoshi Araki’s “The Banquet”)

Japanese artist Nobuyoshi Araki has published more than 500 books over the course of his career. Usually, you won’t find him anywhere near the kitchen – his subjects range from erotic bondage scenes to snapshots of his beloved cat. However, his attempt at a contemporary food photography book may be one of his most poignant works to date.

In 1991, Araki received the devastating news that his wife, Yoko, was quickly succumbing to uterine cancer. An artist at heart, he turned to his camera as a means of overcoming his grief. The result was a publication titled Shokuji, translated as The Banquet. As the name suggests, the menagerie of image and text is a celebration of food. However, it’s far from anything you might find in an issue of Southern Living or Martha Stewart.

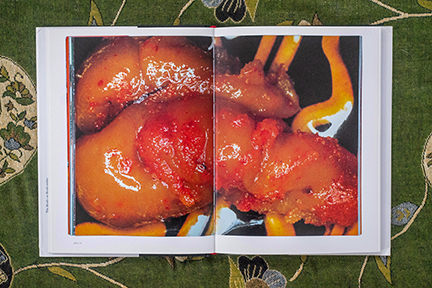

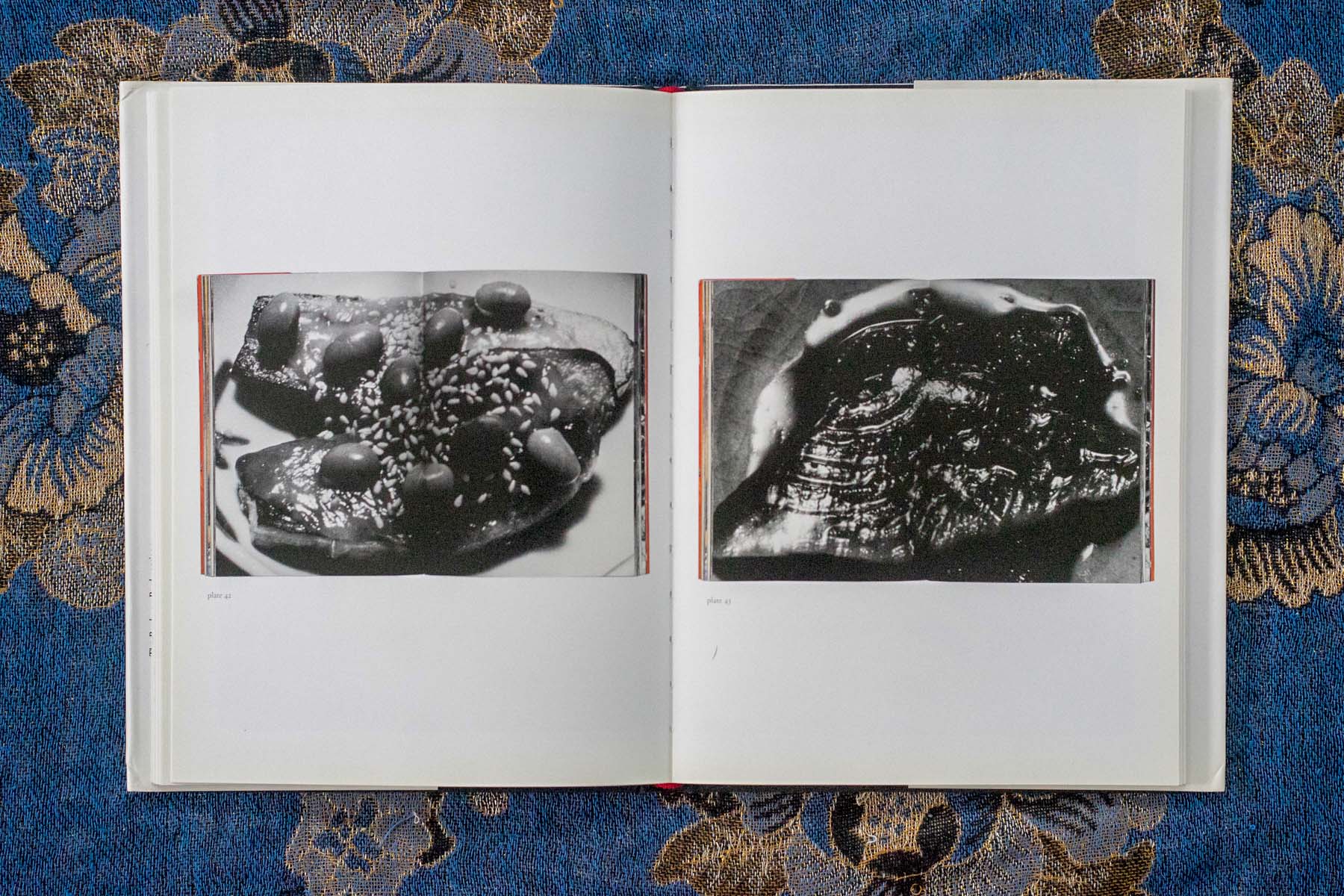

The contemporary food photography book opens with a vibrant collection of imperfect plates. Far from the polished editorial images most of us strive for, we’re forced to hone in on the details that make us most squeamish. Stark reflections bounce off the surface of fresh fish flesh. Oil floats in small spheres atop broth. A slice of buttered toast is already missing a bite or two, far from a pristine presentation.

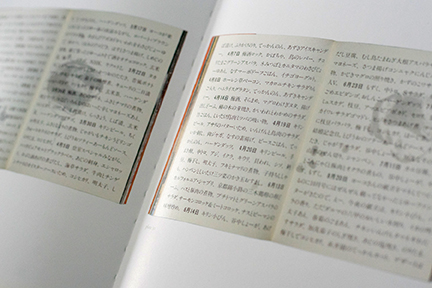

Suddenly, smack in the middle, viewers are privy to a series of diary excerpts. Though the characters might seem exciting and exotic to those unfamiliar with Japanese, the translation reveals that the meaning behind them is anything but. Meticulously listed, Araki keeps track of some of the meals he and his wife share. For instance, an excerpt from January 31st reads as follows:

“Biting into the grilled barracuda meat which opened like legs spreading apart, onion tomato salad, pork and vegetables miso soup…Perrier, Yoko had Kagome Oolong tea made with mineral water because she said it wouldn’t be nice to have beer alone.”

Among the sweet, savory, and sour flavors, readers witness bits and pieces of the bond husband and wife shared. Of course, as anyone with a long term lover knows, intimacy doesn’t always manifest in the form of erotic sex acts. Sometimes, it’s as simple as enjoying the presence of one another over a homemade meal and a pint of Häagen-Dazs, your favorite sitcom humming away in the background.

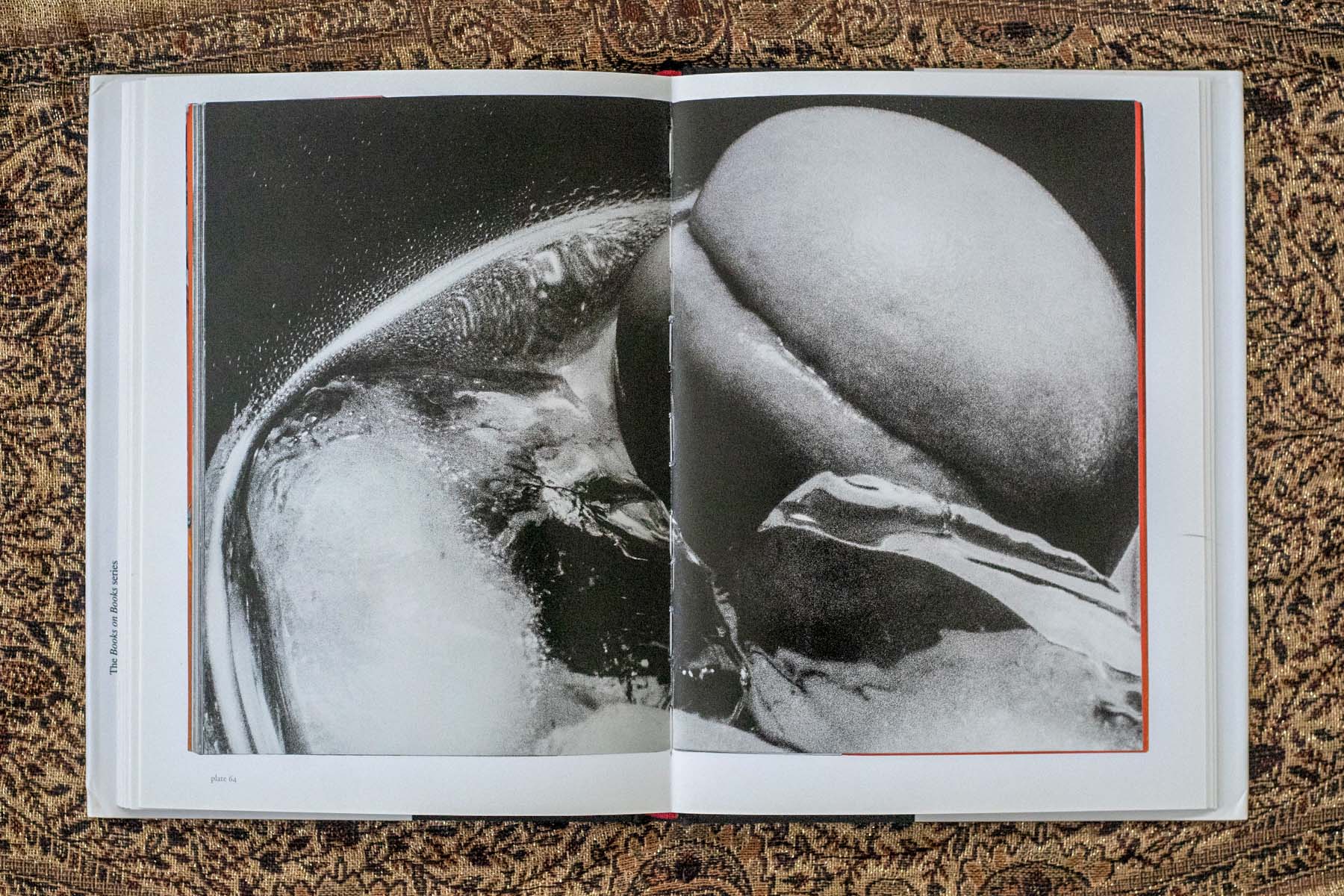

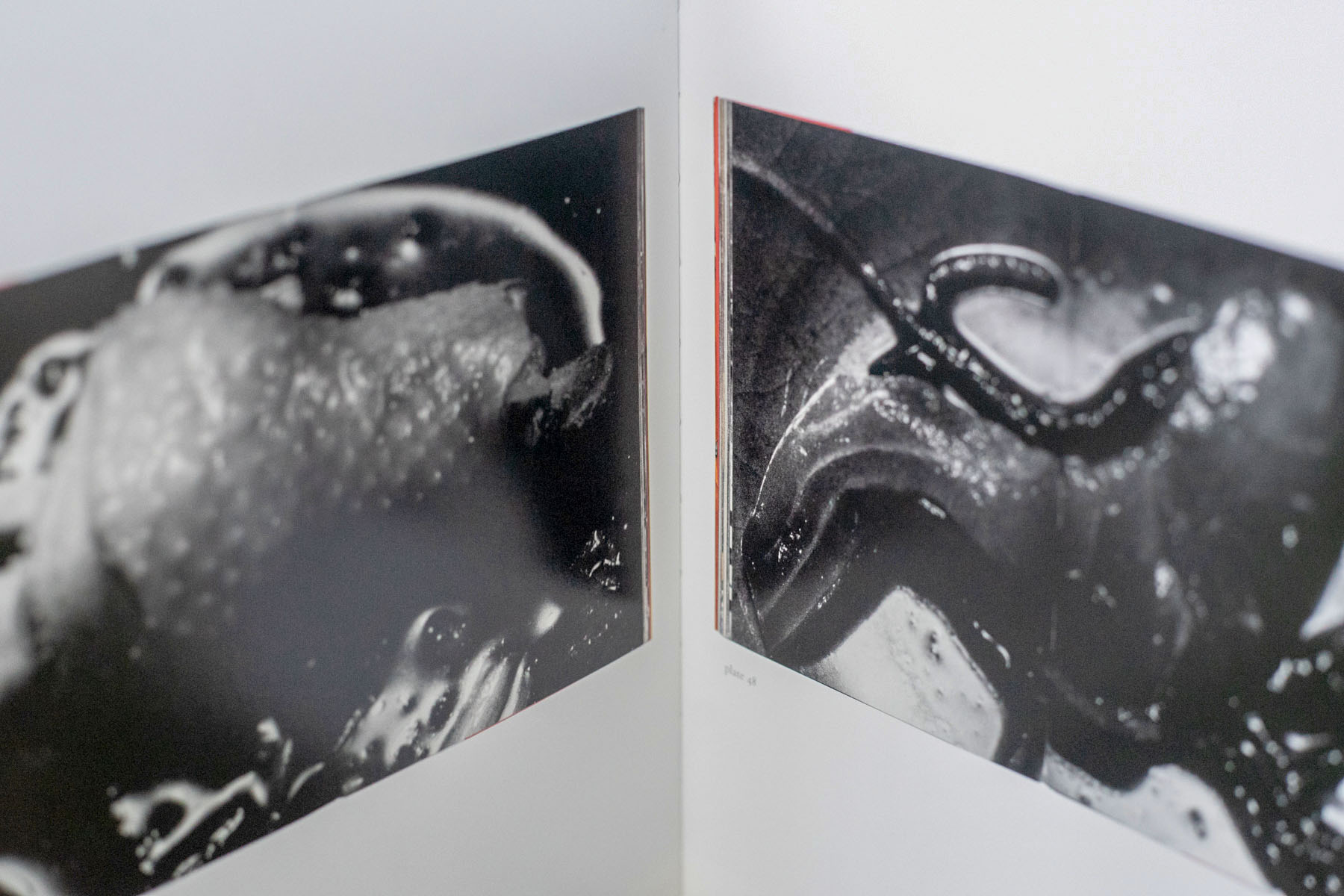

The book’s third and final act returns to food, this time in stark black and white. These images represent the last meals Yoko prepared before surrendering to her illness. They’re messy, almost invasive, and at times shaky. Abstracted, the compositions are hardly recognizable as food. All the same, they’re raw, captivating in a way that a polished product cannot be.

Araki’s contemporary food photography book is a humble reminder of how much more a meal can be. Knowing the backstory, there’s an undeniable tinge of sadness to the work. Each meal, in itself, is just as transient as we are. At the same time, there’s a beauty and sensitivity to each frame. This work is a reminder that we connect over food, and in our darkest times, it’s a source of comfort. At it’s core, The Banquet isn’t just about consumption. Instead, it’s a celebration of love triumphing over loss.