The Sad and Soulful Food Still Lives of David Shterenberg

It’s no secret that historically, still lives as a whole have suffered as the red-headed stepchild of the art world. Throughout history, they hardly made the walls of prestigious galleries, and wealthy patrons rarely commissioned them for their lavish estates. Even today, they’re often relegated to dusty thrift stores and neighborhood garage sales. So, why would anyone bother painting banal, everyday objects when a paintbrush makes it possible to give life to something beautiful and sublime?

Ukranian-born Russian painter David Shterenberg believed that banality was precisely what made an object beautiful. While many Russian artists of the early 20th century focused on bold abstracts and glorified proletariats, Shterenberg instead drew inspiration from the simple things that helped him get through each day.

Even as a young man, Shterenberg showed creative promise. So much so that he pounced at the opportunity to leave home and study fine art in Odessa. As his skills developed, he moved across Europe through Vienna and Paris. There, he had first hand exposure to emerging avant-garde works. Before long, his signature planar style was born from a deep admiration of the Cubist Movement as well as Post-Impressionist pieces by the likes of Cezanne.

The Russia Shterenberg returned to after completing his studies was not the place he had left behind. The Revolution of 1917 had violently uprooted the tsar, paving the way for the Bolsheviks to take the reigns of leadership. The impending civil war would take the lives of thousands of soldiers. Peasants faced food shortages as they tried to navigate the sudden changes. The artist had hoped to settle down in the restless country. Instead, he found himself on the same precarious ground as millions of other Russians. The only way he knew to respond was through his artwork. And, like many of his countrymen, hunger was at the forefront of his mind.

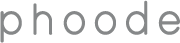

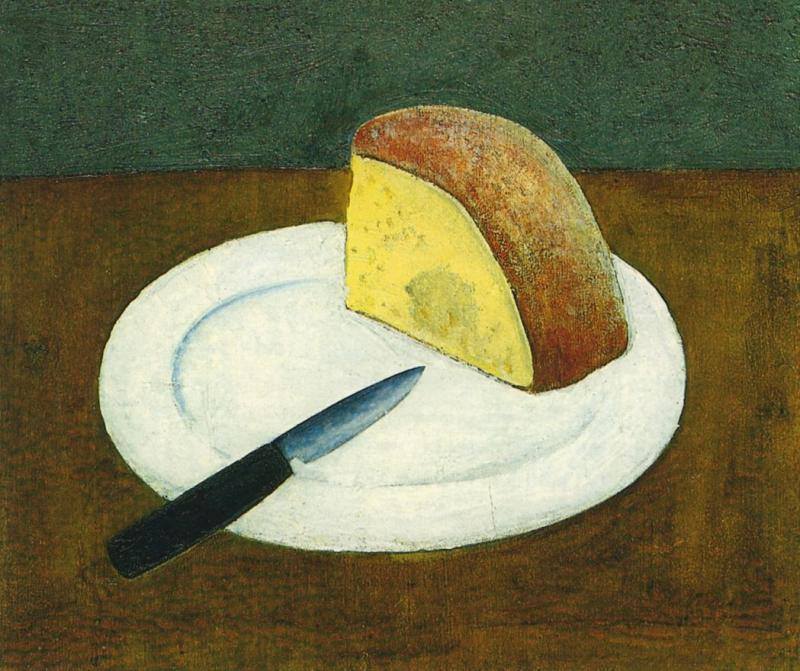

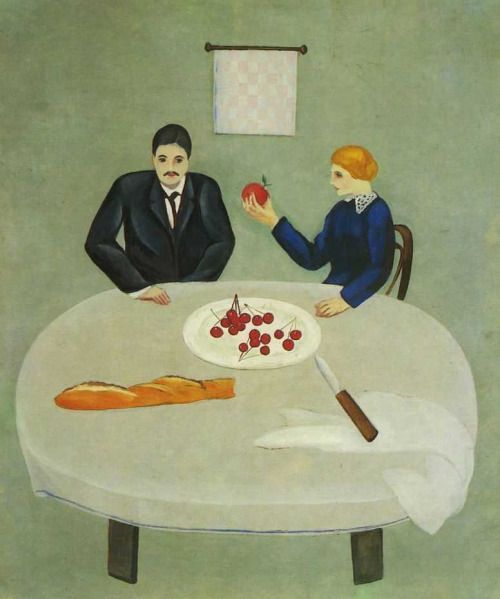

The best word to describe a David Shterenberg food still life is hungry. I know, this may seem a bit contradictory. However, the artist’s compositions masterfully convey the feelings of emptiness and discomfort that come with the physical condition. A brief glance reveals that his still lives hardly resembled the rich, opulent feasts his predecessors painted. Instead, he’d use dull, dark colors to conjure images of stunted root vegetables and fish that seemed to be more bone than meat. Half eaten loaves of bread and sparse fruit plates were the fuel that sustained peasants and artist alike. And, much like the food itself, each piece was simple. Just as a starving person might yearn for a second helping of supper, the expansive negative space present in each canvas leaves viewers wanting more.

Although the subject matter itself is humble, Shterenberg placed the few provisions he had available on a pedestal. At a time of scarcity, the value of the food that people had once taken for granted suddenly became apparent. His art stood in quiet opposition to the propaganda-heavy Socialist Realism being funded by the government, a sign of discontent among the masses. Naturally, those in power disapproved of the truth deep within the artist’s canvases. As a result, the works gradually disappeared from the public eye.

Although he may have died in anonymity, every David Shterenberg food still life sends a powerful message. On the surface, his art seemed modest, nothing more than the meals of ordinary people. In reality, the food he embraced came to represent more than something to be consumed. Each empty table, set of tired eyes, and meager meal offered a rare glimpse into the hearts and mind of an uncertain nation.